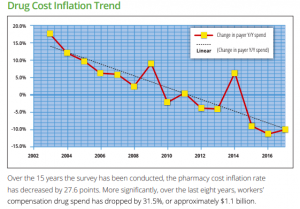

With all the attention being paid to pharmacy prices, it’s time we dug deep into PBM pricing, rebates, and what this all means to you.

We’ve learned from all the lawsuits, Congressional hearings, media blitzes and punditry is that this is everyone else’s fault.

We’ve heard that Ohio is suing Optum over alleged improprieties related to the state’s work comp and Medicaid pharmacy programs [to be clear, Optum’s Ohio work comp problems arose from Optum’s acquisition of Catamaran, which served BWC. The ensuing debacle was not due to Optum’s work comp PBM.]

We’ve heard testimony before Congress that it’s the manufacturers’ fault, the PBMs’ fault, the gubmint’s fault, employers’ fault.

To unpack the issue we have to begin with the list price of drugs vs the actual price.

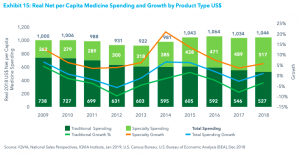

And we have to separate brand drugs vs generics; most of the press about prices pertains to brand drugs. These are medications that are still covered by patents; only the patent holder can sell the drug, and they can set any price they want. In work comp, brand drugs account for about 15% of scripts, but a bit over half of total drug costs; as the manufacturer has monopoly pricing power, that’s not surprising.

(Generics are drugs that have lost patent protection and can be made and sold by any FDA-approved manufacturer.)

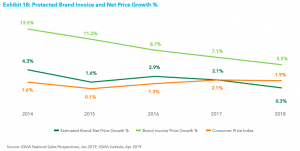

In work comp, most states with fee schedules use “Average Wholesale Price”, a metric that is published by several entities- Medispan is one of the more common. It’s critical to understand that AWP is NOT the real “average wholesale price”, it is merely the price the manufacturer sent to Medispan et al. There’s no checking, auditing, or verification of this price by any outside entity; there’s no independent confirmation that the manufacturer’s AWP is what it charges for the pill.

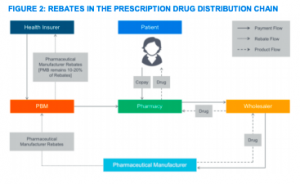

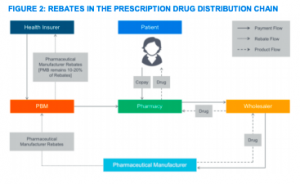

To estimate the actual price, one has to factor in rebates and other financial mechanisms used by manufacturers to market their drugs. Rebates are paid to Pharmacy Benefit Managers – that then pass most of the rebate $$ along to employers and insurers – to encourage the PBM to “put the drug on formulary.” In English, that means the PBM makes it easy and cheap for you, the consumer, to get that medication.

source – Milliman

If a medication is not on a preferred formulary, it will cost a lot more, and you have to go thru the “prior authorization” process to get approval for it.

Clearly manufacturers are highly motivated to get their drugs “on formulary” – and they use rebates to incent PBMs, insurers, and employers to do just that.

So, when calculating the price of the pill, one has to factor in the rebate paid to the PBM/insurer/employer to get to the TRUE price – which is usually a lot less than the published AWP price.

Tomorrow, what this actually looks like – and a few more pricing definitions.

What does this mean for you?

Rebates are critical to understanding pharmacy pricing.