Several years ago the CBO (Congressional Budget Office) predicted the Affordable Care Act would negatively, if minimally, impact employment. Since then, there’s been much parsing of employment data – and way too much credence given to anecdotal reports – by ACA lovers and haters alike. Much of this has been focused on ACA provisions that ostensibly incentivize employers to shift full time workers to part time (<29 hours per week on average).

There’s been much distortion of the CBO’s report as well, most from ACA haters (here, here, and here are just a few examples; a thorough discussion of the issue is here).

In reality, it is still too early to tell what, if any, impact on employment ACA has had. That said, the most credible information available indicates at most a few hundred thousand workers have seen their hours reduced by employers seeking to avoid insuring those workers.

(I would note that these decisions are not eliminating the cost of health care for their workers and dependents, rather they are shifting the cost to the taxpayer and local health care delivery system (most notably hospital ERs and Community Health Centers))

Moreover, it is and will be very, very difficult to separate out the impact of ACA from that of other economic factors affecting employment such as trade patterns and policies, consumer sentiment, the strength of the dollar v other currencies, global energy markets and the like.

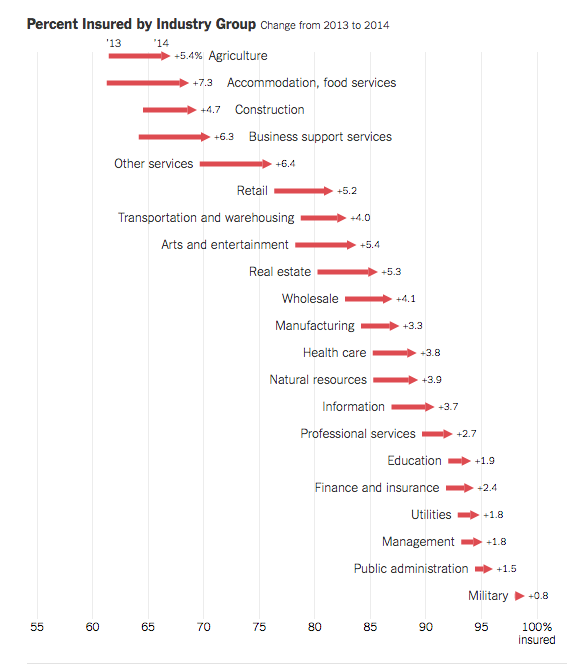

Here’s what we know now.

To date, there’s been little to no change in part-time employment as a result of the ACA. This from a study reported in Health Affairs earlier this year:

[there is] no evidence consistent with the thesis that the ACA caused an overall increase in part-time employment in the United States. Our evidence came from data through 2015, the first year of the employer mandate and the second year of expanded access to coverage through Medicaid expansion and the Marketplaces. As a result, both employers and employees may have still been adjusting to provisions of the ACA.

Another study came to pretty much the same conclusion. While both used slightly different methodologies, neither of which was specifically designed to compare real-world results to the CBO’s predictions, both indicated we haven’t seen hours worked or number of jobs negatively impacted by ACA.

But, that does NOT contradict the CBO.

First, here’s what the CBO said…

CBO estimates that the ACA will reduce the total number of hours worked, on net, by about 1.5 percent to 2.0 percent [and reduce total compensation by about 1 percent] during the period from 2017 to 2024, [emphasis added] almost entirely because workers will choose to supply less labor.

They went on to note that much of this will be voluntary: spouses will reduce their hours because they will gain coverage under their spouse’s plan; some lower-income folks will reduce their hours so they don’t lose out on a subsidy; some will retire early as they won’t lose health insurance coverage previously tied to an employer.

The net…

Because the longer-term reduction in work is expected to come almost entirely from a decline in the amount of labor that workers choose to supply in response to the changes in their incentives, we do not think it is accurate to say that the reduction stems from people “losing” their jobs. [emphasis added]

CBO also opined that the ACA “also will affect employers’ demand for workers, … both by increasing labor costs through the employer penalty (which will reduce labor demand) and by boosting overall demand for goods and services (which will increase labor demand).”

What does this mean for you?

I bring this to your attention, dear reader, in hopes that it helps provide you with a framework to use when evaluating claims that ACA a) is killing jobs or b) has no effect.