So, Liberty Mutual is de-emphasizing workers comp, a move that is increasing profits. But ProPublica/NPR reported “in 2013, insurers had their most profitable year in over a decade, bringing in a hefty 18 percent return.”

Just how “profitable” is workers’ comp? Why is Liberty ratcheting things down while the industry is enjoying its “most profitable year in a decade?”

That’s a difficult question to answer for a number of reasons, but the long and the short of it is; comp is not very profitable.

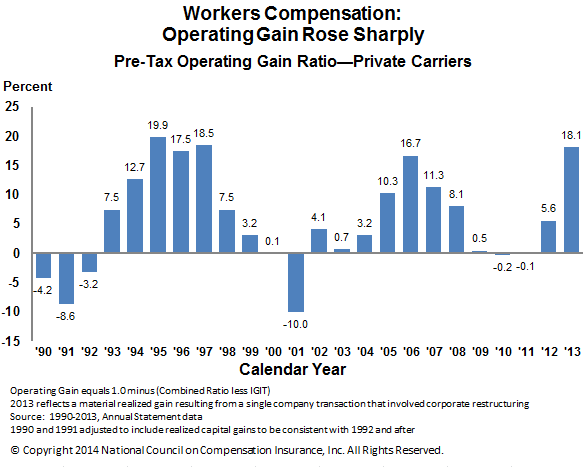

First, the slide that PP/NPR used to make their 18 percent claim.

Let’s parse this out, shall we?

First, there are no perfect measures for calculating WC profitability.

Second, the operating gain is not the same as “profitability”.

Operating gain as a measure has several limitations, not least of which is annual operating gain figures jump around quite a bit for reasons completely unrelated to core financial returns. For example, 2013’s “gain” was significantly increased by one very large carrier’s internal financial transfer, a transfer that, in and of itself, was responsible for several percentage points.

Using a multi-year operating gain (OG) ratio is more meaningful than using a single year as it reduces the effect of one-time financial events. The average NCCI OG ratio from 1990 to 2013 was 5.8%, with a maximum of 19.9% in 1995 and minimum of -10.0% in 2001. The most recent 5 and 10 year averages were 4.8% and 7.4% respectively.

A couple other factoids – The NCCI OG ratio only includes private carrier results, a subset of the total industry. State funds (which tend to be MUCH less profitable) are excluded from the calculations. In addition, the NCCI OG ratio is pre-tax.

Finally, investment income (one key component of operating gain) can’t be allocated to one specific line of coverage (except if the carrier is a mono-line WC insurer). Reserves and other funds are put into a single “bucket” and invested by the insurer in a variety of instruments. Then, when funds are needed to pay claims, they are withdrawn.

So, what metric should be used?

The estimable Bob Hartwig PhD of III, in a piece questioning PP/NPR’s claim of profitability, suggested return on net worth;

According to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners, workers comp return on net worth was just 7.2 percent that year [2013], less than half the figure cited in the article. The average return over the decade from 2004 through 2013 was just 7.1 percent. The returns over that 10-year span ranged from 3.9 percent in 2010 to 10.1 percent in 2004

(PP/NPR’s response is here)

There’s more on the return on net worth discussion at III, in addition to a chart depicting financial returns for other industries. (the metric is also known as return on equity [ROE]).

By way of comparison, you can find representative industry ROE figures from Yahoo.

What’s the net?

Relative to other industries workers’ comp is not terribly financially rewarding. Many industries deliver much better returns.