A long list of real and very difficult problems face California’s legislators; no where on that list is worker’s compensation.

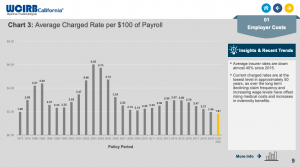

- Work comp premiums are at an all time low,

- injured workers have no trouble accessing care,

- are generally satisfied,

- benefits are good and indemnity payments up by half a billion dollars since reform,

- fewer workers are getting hurt or sick at work which means claims counts are dropping,

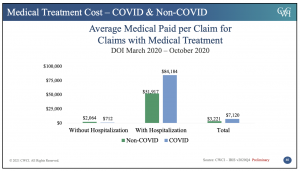

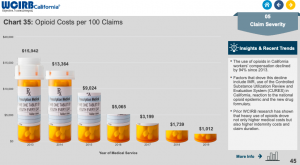

- medical costs have actually declined,

- opioid prescription volume has plummeted, and

- even the IMR mess seems to be improving.

Oh, and rates are dropping again.

Not satisfied with leaving a good thing alone, two legislators are pushing to end all this good news. They’re proposing to return California’s comp system to the awful old days of rampant medical inflation, profiteering by a few shameless medical providers, rapidly rising premiums and much higher costs for taxpayers and employers.

What’s not to love?

AB 1465 is not a solution in search of a problem, rather it creates a problem – one identical to the problem we had before workers’ comp was reformed.

In essence, AB 1465 would allow any doc – regardless of their knowledge of workers’ comp – to care for any workers’ comp patient who seeks them out. Employers and taxpayers would NOT be allowed to negotiate reimbursement, nor would they be allowed to evaluate physicians’ actual performance. (correction thanks to a diligent reader – thanks Sara!)

The bill’s sponsors claim there’s an “access to care” issue that prevents patients from receiving care.

No, there is not. There is no credible evidence that access is an issue – no studies, research, or data whatsoever. If you have any, please share.

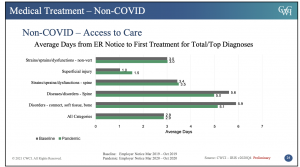

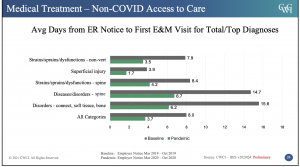

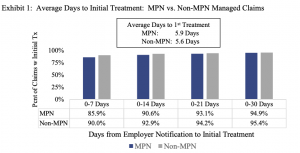

Quite the contrary, there is NO significant difference in access to care for patients treated within or outside a Medical Provider Network.

This from CWCI’s report…

Similarly, there was no significant difference in distance from the patient to provider between MPN and non-MPN patients.

Solving this non-existent problem of access to care will cost California’s employers and taxpayers an additional third of a billion dollars.

But wait, there’s more.

Enabling any Tom Dick or Mary MD to treat workers’ comp patients will almost certainly lead to delays in return to work, higher medical costs, and lower recovery rates. Volumes of research show the more experience a doc has with workers’ comp, the better the outcomes. The contrary is true as well – the less the experience, the worse the outcomes.

I love California. The quality of life is generally excellent, services are generous and pretty good, it is beautiful and diverse and productive, the education system is among the best and higher ed is terrific.

It also has more than its share of problems, some created by stupid policy (restrictions on taxation, fire prevention initiatives, a poorly maintained electrical grid), others by all of us (climate-change-exacerbated wildfires and drought), a really problematic water situation, a major homeless population challenge, wildly expensive housing, awful traffic, and a complete inability to do important things like connecting cities by fast and efficient rail.

With fire season approaching and the grid in dire need of a major upgrade legislators should spend their very limited time fixing those real issues – not creating more problems. I have no idea why these two legislators think a non-existent “access to care” issue merits increasing employers’ and taxpayers’ costs by a third of a billion dollars.

And I don’t think they do either.

What does this mean for you?

If you do business or are a workers’ comp patient in California, you’ve got to kill this bill.