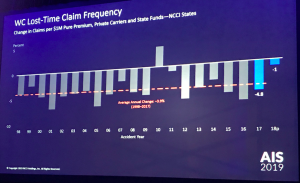

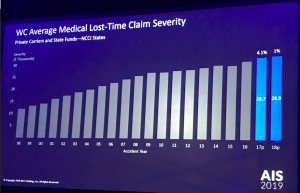

The generic drug manufacturers’ price-fixing scheme raised prices by up to 1,000 percent. There’s good news for workers’ comp payers as the impact has been minimal.

Here’s why.

Workers’ comp is mostly about trauma treatment and pain management; relatively few drugs are involved. Contrast that to Medicaid, Medicare, and health insurance which cover all conditions – and have a much broader “formulary”.

Contrary to what others have opined, this didn’t have any significant impact on workers comp, because there were very few “work comp” drugs affected by the price-fixing.

Here’s more from my conversation with Jim Andrews, RPh.

MCM – In your view how did the alleged price fixing affect workers’ comp payers?

Andrews – Since WC utilizes specific drug classes the impact of these 100 drugs could/would be significantly less than that of the commercial and governmental markets (especially Medicare and Medicaid). A quick scan of these drugs (without reviewing the larger WC PBM annual drug trends) reveals that there are blood pressure medications, antibiotics, birth control, dermatological , blood thinners etc. I do not see (might have missed it) – narcotic pain medications.

So the overall cost impact from this companies’ activities do not significantly impact WC by themselves.

MCM – What medications commonly used in workers’ comp may have been involved?

Andrews – Generic Celebrex (celecoxib), generic Neurontin (gabapentin) and generic ketoprofen represent some of the more commonly prescribed drugs utilized today.

[These drugs] didn’t seem to detail the same level of price support that some of the other drugs had e.g. pharmacy and GPO involvement.

[MCM – note data from workers’ comp PBMs indicate the these three drugs account for about 7% of total drug spend].

MCM – There’s a difference between drug reference price (AWP, etc) and the actual price paid. Does the report provide any insight into whether the price fixing actually affected the price paid?

Andrews – It is unclear to me whether the purchase price for these channels actually increased or whether the drug reference price e.g. AWP increased.

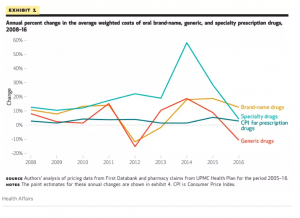

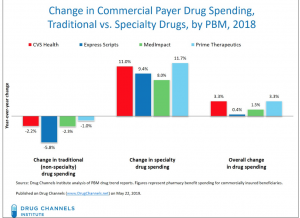

MCM – this from Vox shows changes in overall drug costs over time.

What does this mean for you?

Yes, the price-fixing affected workers’ comp, but not much.

I’d encourage all to read Dr Fein’s post – and to subscribe to

I’d encourage all to read Dr Fein’s post – and to subscribe to