Last month RIMS announced its annual awards; one of the recipients is the risk manager for Cardinal Health, another has a similar role at McKesson.

Awarding awards for excellence in risk management to two individuals at companies with huge liabilities for the opioid crisis, and failing to discuss that liability in press releases is pretty shocking.

Both companies are embroiled in ongoing and likely very expensive litigation regarding their responsibility for the opioid crisis. Cardinal just announced a $4.9 billion loss for the first quarter of 2020, attributing the hit entirely to opioid litigation (the company estimated the cost of litigation at $5.6 billion.

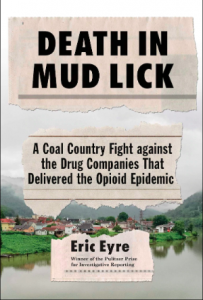

West Virginia is one of the states devastated by rampant overuse of opioids; Pulitzer Prize-winning reporter Eric Eyre just published a book detailing his investigation into Cardinal’s role in the opioid crisis.

According to Eyre, Cardinal “saturated the state with hydrocodone and oxycodone — a combined 240 million pills between 2007 and 2012. That amounted to 130 pain pills for every resident.” All told, distributors shipped 780 million pills into West Virginia over that time.

Cardinal, McKesson, and Amerisource Bergen are the largest drug wholesalers in the nation, acting as the middlemen between manufacturers and retail and mail order pharmacies. While all three contend they are just part of the supply chain, they are required to monitor and report shipments of controlled substances – including opioids, a responsibility that is at the center of the litigation.

(This is not to say the three distributors bear all the responsibility for the crisis – far from it. State health officials, the DEA, FDA, prescribing physicians, opioid manufacturers and others all share in that responsibility.)

From the Washington Post:

McKesson, Cardinal Health and AmerisourceBergen, were in and out of court. They paid lots of fines but kept on trucking. In 2018, their chief executives gave sworn testimony before the House of Representatives Committee on Energy and Commerce: All denied contributing to the opioid crisis. Later that year, the committee released the results of an 18-month study. It found that distributors failed to conduct proper oversight of pharmacies by not questioning suspicious activity and not properly monitoring the quantity of painkillers shipped. [emphasis added]

Earlier this year, McKesson agreed to pay investors $175 million to settle claims that “directors failed to maintain adequate internal systems for spotting suspicious opioid shipments…” According to Bloomberg, U.S. District Judge Claudia Wilken in Oakland, California said the suit raised:

“legitimate questions about whether directors ignored “multiple red flags” about opioid shipments even after agreeing to step up compliance oversight as a result of a deal with the government.

The settlement, produced in part by a series of mediation sessions, calls for McKesson to add two new independent directors to its board, to beef up compliance training for directors and improvements in internal systems designed to red-flag suspicious orders, according to court filings.”

McKesson is the also the subject of a criminal probe launched by Federal prosecutors in Brooklyn, NY.

So, the world’s leading risk management organization conferred prestigious awards on risk management professionals at two companies that have massive financial liability – and I would argue ethical responsibility – for what can only be described as a massive risk management failure. And one is the subject of a Federal criminal probe.

I contacted RIMS to inquire about the decision criteria used by the individuals to select the award recipients, stating:

I’m curious as to the decision criteria employed by the award committee that resulted in awards to these two executives. While their accomplishments are impressive and their achievements notable, I’d like to understand how the opioid settlement issue factored into the award decision.

RIMS Communications Director Josh Salter was kind enough to provide an initial response:

RIMS awards are reviewed and selected by volunteers. This group of risk professionals is charged with vetting all submissions and then, using their experience in the profession, making a decision based on the applicant’s accomplishments. While the volunteer group changes from year to year, I will share this information with them.

I asked Mr Salter if he would facilitate a discussion with any members of the committee and offered to keep the names of those members confidential; to date and after multiple requests I have not received a response. [I’m certainly willing to hear from Mr Salter and committee members]

Eyre’s editor, Ned Chilton, coined the term “sustained outrage” to define what he saw as an essential responsibility of news organizations, a demand that media keep the focus on injustices instead of reporting on a calamity and moving on. I’ve been reporting on the opioid crisis since 2005; over the last two years my passion and drive has burned out.

That’s my fault.

I struggle to understand how RIMS could confer prestigious awards for “risk management” on individuals at two huge companies that bear significant responsibility for the opioid crisis – and not even mention the opioid issue in publicity around the awards. This is not to impugn the professionalism, ethics, or abilities of the individuals recognized by RIMS, rather to ask a very uncomfortable question, one RIMS needs to address.

What does this mean for you?

We cannot let crisis fatigue take our focus off opioids.

[PS – kudos to Tristar’s Mary Ann Lubeskie for her ongoing and tireless efforts to keep opioids front and center… you can follow her at @maryannlubeskie on Twitter]