Well, some posts get a life of their own, and so it is with this discussion of claims frequency and claims counts. After much discussion with colleagues and several back-and-forth emails with WCRI CEO John Ruser PhD about the correlation of OSHA recordable data and work comp claims and why both are declining, I decided the best way to get this to you, dear reader, is via an interview. So, read on.

MCM – I believe that you were responsible for the BLS OSHA-recordable injury data for years. What are a couple key points readers should know about the OSHA-recordable reports?

Dr Ruser – Yes, I was BLS Assistant Commissioner for Occupational Safety and Health Statistics for over 5 years and was a researcher of the BLS OSHA data for many years before that.

While there has been some controversy about the completeness of reporting in the OSHA recordkeeping system (see below), the BLS OSHA-recordable injury rate data are extremely valuable for several reasons. They are very detailed by State, by industry, by establishment size and by worker characteristics, so that are an important benchmarking tool for risk managers and others seeking to compare their company’s injury rates against their peers. From the perspective of focusing injury risk reduction efforts, they are important in identifying those groups of workers at higher risk of injury and they are used by OSHA to identify high-risk industries for inspections. And, with their long relatively-consistent time series and detail, they are a valuable tool for researchers seeking to understand factors that contribute to workplace injuries.

MCM – Where does BLS get the data for the OSHA-recordable reports?

Dr Ruser – BLS’s estimates of OSHA-recordable injuries are based on a very large annual survey of about a quarter-million establishments (that is, specific locations of a company or organization) called the Survey of Occupational Injuries and Illnesses (SOII). The SOII contains employer-reported data drawn from the OSHA logs that establishments keep throughout the year. SOII covers non-fatal occupational injuries and those illnesses that can be directly linked to a workplace. A separate BLS program, the Census of Fatal Occupational Injuries, uses multiple data sources, such as death certificates, OSHA reports and many other sources, to track workplace deaths due to injury.

MCM – there’s been questions about the decline in reportables over the years. Can you comment on these questions?

Dr Ruser – Some skeptics of the declines in the BLS OSHA-recordable injury rates attribute these declines to changes in OSHA-recordkeeping rules and practices or tightening in WC compensability rules, meaning the declines in injury rates are at least in part an artifact of reporting. External research supported by BLS and other non-BLS-supported research does suggest that the number of injuries captured in SOII undercounts the true number of OSHA-recordable injuries. (BLS has a very complete webpage on SOII data quality research that you can access here: https://www.bls.gov/iif/soii-bibliography.htm)

But, while the numbers (levels) of injuries and claims may be undercounted, the issue for the observed declines (trends) in injuries (and WC claims) is whether underreporting has grown. There is little direct research on this. A study by Washington State comparing SOII data to WC claims found that during the first five years of the study period (2002 – 2006), underreporting decreased, while it increased from 2007 to 2011. Importantly, the Washington State researchers concluded that the total estimated actual number of SOII-eligible WC time loss injuries decreased over the ten year span, meaning there were real declines in injuries (and some underreporting too).

The Washington State study was excellent, but it focused on one state and a relatively short time span, which included a great recession during the second half of the study period when underreporting was identified. Another approach to validating the time trends is to compare to other data that should not be susceptible to the concerns raised about reporting.

MCM – what analyses did you do to explore that issue?

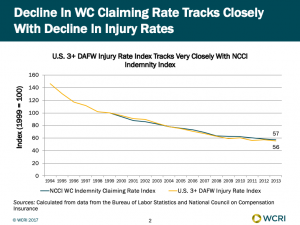

Dr Ruser – I compared the SOII data with data from other sources. First, I looked at how the US injury rate for 3 or more days away from work tracks with the NCCI indemnity claiming rate. The declines in these two data series track extremely closely. So, while the OSHA recordkeeping system is technically independent of workers’ compensation, the BLS injury data and the NCCI claims data are telling the same story and the BLS data can be used to try to identify factors associated with the decline in the NCCI WC claiming rate.

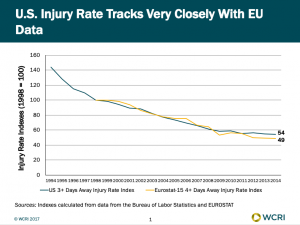

Regarding whether the BLS injury rate decline is real, I created an index of the OSHA-recordable case rate for cases with 3 or more days away from work and lined it up with a similar index for 15 EU countries for injuries with 4 or more days away from work (the series most comparable to the US data). The chart that is attached shows how similar the trends are in the US and in the EU. The index was set to 100 for injury rate values in 1998 and the other values in the chart are injury rates relative to 1998. As of 2014, the US injury rate was 54 percent of its value in 1998, while the EU injury rate in 2014 was 49 percent of its value in 1998.

MCM – what does this mean (for our readers)?:

Dr Ruser- The remarkably similar trends in the US and EU data suggest that we need to look beyond US-specific explanations (such as OSHA-recordkeeping rules or WC compensability rules) to understand what is responsible for the long-run aggregate declines in injury rates and WC claims rates. While there may be some changes in reporting at least over part of the past quarter century, the good news, I believe, is that there has been a remarkable improvement in safety and this improvement is seen in most industries and in many developed countries.

Joe – do you believe that injury rates are declining? I do. As an industry, we can take some credit in the notion of our huge expenditures in loss prevention departments, is having a positive impact on safety. Let’s toot our horn on that a bit. But also, the nature of work has evolved significantly in the last century – we have many more white collar jobs as a percentage of total employment, and automation and process improvements have been dramatic in many industries — just think about how loggers used to do their work 100 years ago, and now many sit in air conditioned machines that do all the dirty work. Under-reporting may be an issue, but what would be the things that cause it to materially increase over time?

Hi Mike –

yes, I do believe injury rates are declining.

There are self-serving reasons for employers to undercount occupational injuries and illnesses, and it is possible employers have become more attuned to those reasons over time. Note I say “possible”; that is a possibility but just that.

Also, as Dr Ruser’s research indicates, there have been declines in injury RATES in ALL industries – so rates for high-frequency industries have come down as have rates for lower-frequency industries. The implication is, as you note, that safety efforts and other factors have led to reductions in all employment types.

In addition, a decline in employment in “high-frequency” industries reduces the total injury COUNT.

Thanks, Joe and Dr Ruser for a very thorough and coherent explanation and conclusion. I appreciate the explanation of OSHA recordkeeping and statistical analysis.

While the similarities between workers’ comp injury rates and SOII estimates and EU injury rates seem to indicate widespread correlation, there have been several scholarly studies that have proven that significant under-reporting of injuries exists.

For example, see http://scienceblogs.com/thepumphandle/2014/11/06/twice-as-many-work-related-skull-fractures-than-government-estimate/. That posting indicates that a comparison of data from acute-care hospitals, workers’ compensation records, death certificates and police reports in Michigan in 2012 showed 316 cases meeting their study criteria, while SOII indicates there were 170 cases. Only 100 of the cases they identified existed in workers’ compensation records.

The same researchers (Kica and Rosenman) had previously studied work-related amputations, and their research revealed that BLS missed about half of them. Likewise, they found the BLS data missed about 70 percent of work-related burns.

My question to researchers everywhere: Has this widespread under-reporting always existed, or have societal forces caused this under-reporting to have escalated over the past 30-50 years?

Hello Arnold – thanks for the comment and research – much appreciated.

I reviewed the Kica and Rosenman presentation on skull fractures in MI, and have a couple observations.

1. It is very detailed research into nuances of skull fracture injuries, causation, Dx codes, etc.

2. One of the key assumptions the authors make is that hospital Emergency Departments are correct in identifying the place of injury and the injured person’s employment status at the moment of injury. ED reports account for the lion’s share of the additional work-related injuries documented by the authors.

I’m a bit skeptical of this; knowing a bit about how EDs work I’d suggest it is indeed possible that there is a significant over-count of “occupationally-related injuries” due to ED intake staff’s level of diligence in establishing location and occupational status. This isn’t a criticism of those staff, rather an acknowledgement that their priorities are patient-care centered and not so much in determining causation/employment status.

Conversely, WC payers and employers are much more focused on those two issues.

That is not to say there isn’t under-reporting, rather to point out one is much more attuned to the “occupational” issue than the other.