When they buy a company, investors are betting the story they’re told is accurate, that it fairly represents future opportunities and risks. They’re betting on management – the people who built the company, that they’re who they appear to be – honest, insightful, decisive, well-connected.

When they get it right, it’s rewarding indeed. But when they don’t, it may be career-limiting.

Investors do diligence – often a lot of diligence – to make those bets as sure as possible. But, most investors aren’t expert in the specific niches occupied by the companies they are buying, so they rely on “Subject Matter Experts.” These are long-time industry people who know the ins and outs; probably know the business and its management; understand markets, regulations, and where things are headed; and have the contacts and relationships who will help give them the real story.

In the ten years or so I’ve been doing this, I’ve learned a lot. Here are a few takeaways.

Dig Deep into the Details

The proof is in the details. Dig deep into the stuff that drives the financial results. Investors are really good at financial analysis, but they don’t understand what drives those finances. Things like procedure codes, billing processes, discount arrangements, fee schedules, workflows and systems connections are where the business succeeds or fails.

Example – Read the actual provider contracts. What do they cover? What are the rates? What is the time frame? Compare the contracts to those provider’s bills – do the billing results match the contractual terms? Is the patient a member of a contracted customer? Did the customer do what was required to “earn” the discount?

If the seller won’t get into those details, you’ve got to ask why. Either A) they don’t have that information available, which is troubling in and of itself, or B) they have it but don’t want to share it, which is also troubling, and/or C) they are paranoid their “secret sauce” will become not-so-secret.

Push, and push hard. Make very sure your client knows exactly why this information is critical.

Pay attention to…

Overnight successes. Businesses that sort of float along, then experience a sudden jump in profits and/or revenues need extra-careful analysis. The seller will claim this was all part of the plan, they built carefully, invested heavily, and now are seeing the benefit of that strategy.

Perhaps…and perhaps there’s been some deep cost-cutting, a change in how they determine what’s revenue and when they can recognize it, a shift in accounting for old receivables, a new billing process. That’s not to say those things are inherently bad, they just may not reflect anything more than a one-time bump, or they may not be sustainable, and/or their suppliers (in many cases these are healthcare providers) may decide they don’t like whatever’s changed.

Vague claims. Stuff like “we keep all our customers”, “our program is clinically based” – where’s the supporting documentation? If the seller says it, they should be able to back it up convincingly.

The SME’s job

The seller will do a fine job of “selling”, my job is to be the realist.

In my view, my job is not to blow sunshine up the buyer’s shirt, but rather to find the potential issues, problems, roadblocks, and concerns and clearly illustrate what they are, the potential implications, and how much of a problem they represent.

There’s a lot of pressure on investors to do deals. They’ve taken millions of investor dollars into their funds, and need to park it somewhere. As potential deals become scarcer and more expensive, the pressure increases.

Strive to be just a bit on the skeptical side, and you’ll serve your client well.

Stick to what you know

I’m often asked “would you invest your money in this business?” To which I reply, “Look at my investment portfolio and you’ll see why I’m the wrong person to ask about investments.”

Point being, buyers value companies for reasons that escape logic, or at least what I think of as logic.

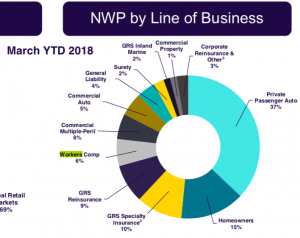

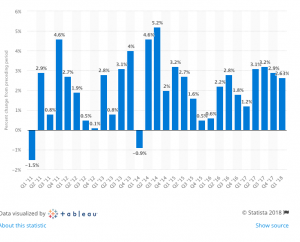

For example, there’s CorVel. Why this company has a price:earnings ratio of 30 is beyond me. Revenue growth is minimal, operating income grew 10 percent in 3 years…hardly a growth company worthy of that multiple. But hey, what do I know.

Instead, focus on the business itself – let the investors figure out what it is “worth” – they understand valuation, I don’t.

Be clear about your biases

As you know all to well, dear reader, I have strongly held opinions. You should too. Be very careful to support your opinions with facts, based on data, supported by logic. Be transparent to your client.

That doesn’t mean you don’t share your views, just be clear about what they are, and on what they are based. That allows the client to assess how they should value your view on that issue.

One advantage of spending decades in a business is you just know stuff, you see things and instantly have a sense that this is BS, or wow, this is innovative, or huh, that doesn’t look right. You can’t exactly put your finger on it, but it’s there.

Your client is paying you for those decades of experience, the judgment it brings, and must know how you arrive at a conclusion, statement, or opinion. Telling the client that something just doesn’t feel right is fine – but understand they’re going to push you hard to figure out why.

Tomorrow, a couple other things I’ve learned

What does this mean for you?

It’s critical to be critical.