To hear hospital lobbyists talk, you’d think Florida’s taxpayers and employers should subsidize hospital losses by paying exorbitant amounts for hospital care.

Yesterday’s virtual meeting of the State’s Three Member Panel (TMP) featured several hospital lobbyists and officials waxing poetic over proposed changes to workers’ comp facility reimbursement, citing the changes’ “fairness”, describing the TMP’s proposal as a “win-win” and the proposed changes as “reasonable”.

Ha.

After Hoovering hundreds of millions out of taxpayers’ and employers’ wallets for years, some hospitals want to continue forcing those taxpayers and employers to pay rates that are often 8 to 12 times what Medicare pays. They cited an NCCI analysis that purported to show big system savings.

Unfortunately the analysis itself appears to be a state secret as it hasn’t been shared…so no one except NCCI and the Three Member Panel know what data was used, what time period it covered, the methodology employed, or anything else. That’s unfair to NCCI and to every stakeholder, unwise politically, and unhelpful as parties who like the finding can’t cite specifics, and parties that don’t like it can dismiss it outright.

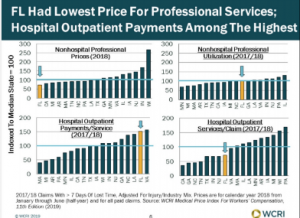

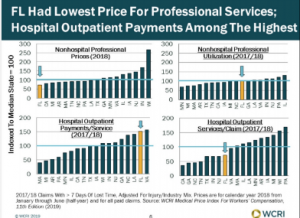

What these hospital advocates didn’t discuss was the basic unfairness of Florida’s work comp physician reimbursement. WCRI data indicates the State’s docs, PTs, OTs, chiros, and other clinicians get paid less than their colleagues in every other state in WCRI’s report. The changes proposed by the TMP would increase providers’ reimbursement by a whopping 0.9%.

As WorkCompCentral’s Will Rabb reported in an excellent summary of the call, the TMP is somewhat limited by statute, a challenge noted several times by Ass’t Director, Dept of Workers’ Comp Andrew Sabolic. However, Mr Sabolic’s words to the effect that it isn’t possible to define or determine “reasonable” (a statutory criterion for determining reimbursement) are puzzling. I’d suggest an analogy might be helpful (wish I’d thought of this while testifying on the call yesterday…)

Think of it this way; you pull into a gas station – which doesn’t post gas prices – in your personal car, fill up, and only after you’re done do you find out what you have to pay.

If you pulled into an HCA station, you’re going to pay about 8 times what the driver in front of you who filled up their government-issue car pays.

Under the per-diem plus outlier scheme that is kind of/sort of in place today (although many payers are basing reimbursement on a Court ruling essentially eliminating outlier payments) HCA – and some other mostly for-profit hospitals and health systems – get paid 8+ times Medicare rates. And that was based on data from 2016; I’d suggest that it is highly likely you are paying even more today.

By any “reasonable” definition that is wildly “unreasonable”.

(A detailed discussion of this is here and here is an excellent report by Johns Hopkins researchers on Florida facility costs (non-subscribers to HealthAffairs have to buy it, but the summary is free)

I won’t get into the bizarre multiplier scheme proposal; suffice it to say that it is unique, hasn’t been used in any other state, is not based at all on what it actually costs a hospital to deliver services, and is completely game-able; any hospital can increase their reimbursement by a factor of 5 just by increasing their charges.

I will note that many hospitals don’t wildly overcharge work comp payers; many – but not all – not for profit facilities get paid less than 3 times Medicare.

What does this mean for you?

How is this “reasonable”?

If you want more info on why some hospitals are supporting this scheme, see here.

The TMP will meet December 17 to discuss implementing the changes; you can register here.